lecture series

history of american architecture: utopias

Tuesdays, February 18 through March 18, 2025

Virtual | 12:00pm-1:15pm EST

Virtual and In-Person | 6:30pm-7:45pm EST

In-Person at Cranbrook Art Museum de Salle Auditorium

Lecturer: Kevin Adkisson, Curator, Cranbrook Center for Collections and Research

$85 for Adults; $25 for Full-Time Students with ID

Free for Cranbrook Students (email center@cranbrook.edu)

Advance registration is required (fee includes all five lectures)

This lecture series is eligible for American Institute of Architects Continuing Education Credits (AIA/CES)

Presented by Cranbrook Center for Collections and Research

Join Kevin Adkisson for the return of the Center's popular History of American Architecture lecture series. The eighth annual installment will study utopias, and their role in shaping modern architecture.

The 2025 History of American Architecture Lecture Series is sponsored by the Michigan Architectural Foundation (MAF) through a Damien Farrell Architectural Awareness Grant.

What is utopia? Why have successive generations of architects, planners, philosophers, and polymaths envisioned or attempted to build utopia? From the Renaissance to Colonial America and through to Silicon Valley, the search for a more harmonious existence between citizens, nature, and architecture is a perennially rich problem.

In this series, we will examine ideal cities and model suburbs; religious and educational experiments; communal and intentional communities; and more. Utopian visions have given form to radical experimentation in architecture. Even if utopia itself remains elusive, the wider field of architecture and design has been repeatedly shaped by the search for the perfect society.

Each week will introduce new utopias—from ideas and plans to buildings and entire cities—in a 75-minute, image-rich lecture that draws from the resources of Cranbrook Academy of Art Library and Cranbrook Archives. All are welcome to attend this engaging series: students, curious beginners, seasoned enthusiasts, or design professionals.

About the Lecture Series

Week One

We begin with the ideal cities of the Renaissance: geometric plans from Leon Battista Alberti and Filippo Brunelleschi, which suggest harmony, order, and the perfect society. These ideal visions informed Colonial America, from Spanish California to French Louisiana and New England. By the mid-19th century, charismatic individuals and religious converts attempted to create new forms of ideal communities, each with their own architectural expression. New Harmony, Indiana (1825), Salt Lake City, Utah (1847), Oneida, New York (1848), and Amana, Iowa (1855), all proposed new ways of living. With simple forms and innovative buildings (plus clothespins and paper bags), the Shaker communities of New England and the Midwest achieved an aesthetic highpoint in American utopias.

Week Two

Contrasting Shaker simplicity were capitalist utopias attempted by Pullman, Westinghouse, Ford, Edison, and others. The heady mix of urbanization, industrialization, and the eclecticism of Victorian architecture stirred strong reactions and a desire to forge an alternative path. Arts and Crafts communities—from idylls like Roycroft (1895) and Byrdcliffe Colonies (1902) or Craftsman Farms (1915), to urban institutions like Hull House (1889) and the Detroit Society of Arts and Crafts (1906)—allowed architects and designers to find new expressions for modern living. The Cranbrook Institutions (1927-1932) would emerge as a late and exquisite flowering of Arts and Crafts ideals (and the site of ever-renewing student utopias).

Week Three

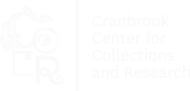

Between the wars, architects in Europe proposed new communities in radical forms. Le Corbusier's Radiant City (1924), Walter Gropius's Dessau Bauhaus (1925), and Moisei Yakovlevich Ginzburg's constructivist Narkomfin Building (1929) provided modernist models for future growth. In England, Ebenezer Howard's Garden City Movement laid out a different model: the village perfected. In America, garden suburbs sprang up in every state (including Radburn, New Jersey, a "Town for the Motor Age") while the architecture of World's Fairs proposed radically new ways of building that captured the public's imagination. With technological advances and a booming economy, could postwar America become utopia?

Week Four

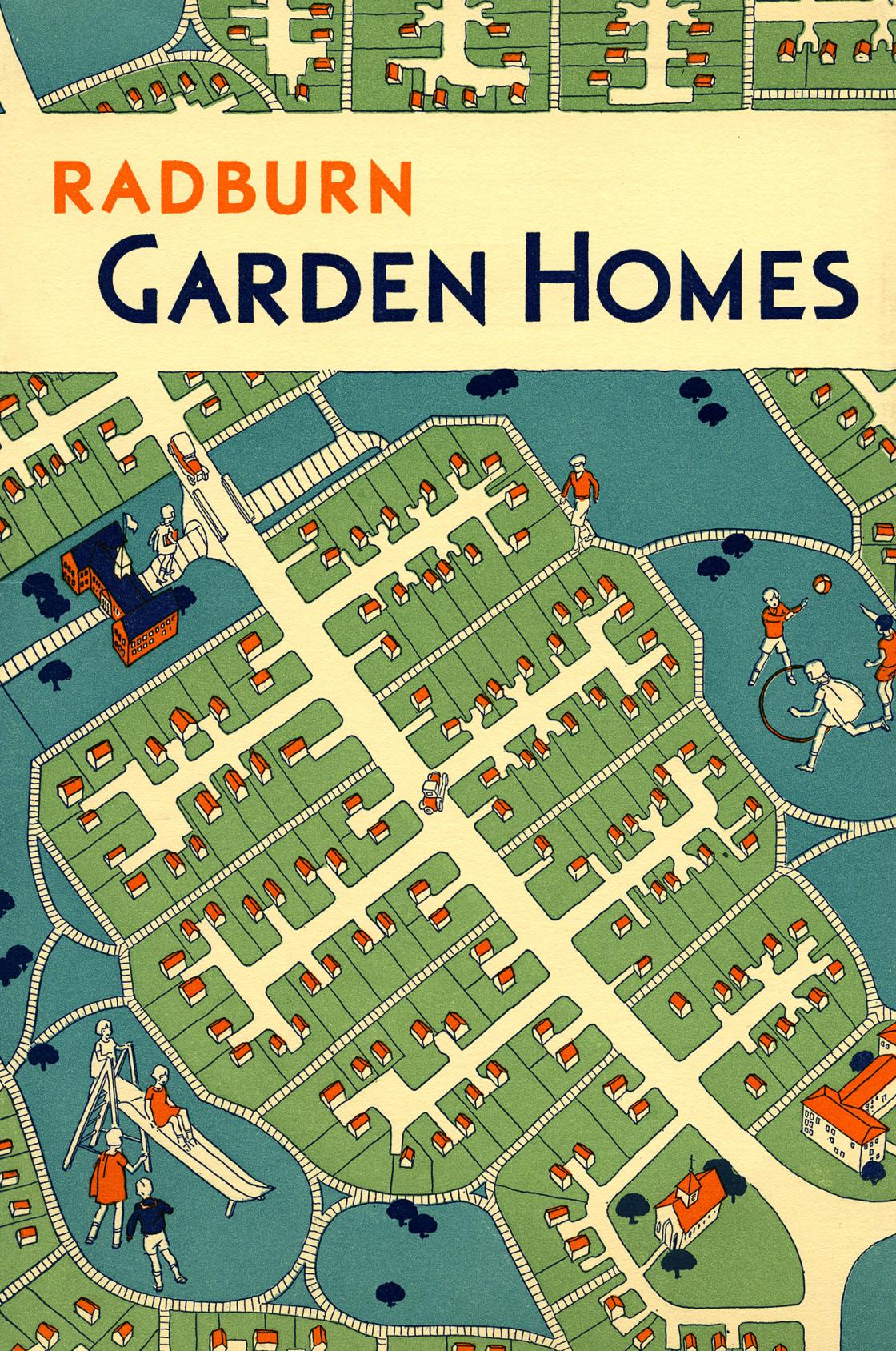

From the eternal spring of Victor Gruen's enclosed shopping malls to Eero Saarinen's General Motors Technical Center (1956), new postwar building types suggested a capitalist utopia was possible. Walt Disney's Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow (1966) held the promise of a new, more perfect city in Florida. But resistance to the shine of American capitalism and its sleek modernist vocabulary was growing. Architecture schools and architectural collaboratives across the country became sites of formal resistance to established norms—deploying mud bricks, recycled materials, mylar sheets, spray foam, or inflatables in construction. Drop City (1965) near Trinidad, Colorado, Project Argus (1968) in New Haven, Connecticut, or The Farm (1971) in Lewis County, Tennessee, proposed distinct utopian futures. The most iconic and ambitious plan of the period was Paolo Soleri's Arcosanti (1970). Developed along his principles of arcology (architecture and ecology) in the Arizona desert, Soleri built dense urban living with minimal environmental impact in iconoclastic, structurally daring form.

Week Five

The end of the twentieth century saw two utopian-adjacent architectural developments: the environmental movement's successes in developing sustainable buildings, and the New Urbanist movement in community planning (seen, splendidly, in Seaside, Florida, 1981). But are architects speculating on utopia today? In a moment of global instability and wealth inequality, American architects have turned inward. Contrasting mega-developments in the Middle East (for example, NEOM, Saudi Arabia, or Masdar City, UAE) the visionary American architect has turned again toward speculative proposals over the built form. As in the Renaissance, American architectural thought has returned to imagined forms in order to point toward a different future.

ABOUT KEVIN ADKISSON

Center Curator Kevin Adkisson works on preservation, interpretation, and programming across the many buildings and treasures of Cranbrook. Since arriving as a Collections Fellow in 2016, Kevin has welcomed thousands of guests to Cranbrook's National Historic Landmark campus, both in person and virtually. Kevin makes history come alive with a friendly, humorous nature, and a deep passion for architecture.

Kevin earned his BA in Architecture from Yale, where he worked in the Yale University Art Gallery's Garvan Furniture Study. Kevin received his MA from the University of Delaware's Winterthur Program in American Material Culture, with a thesis examining the role of postmodernism in shopping mall architecture.

Before coming to Cranbrook, Kevin worked for Robert A.M. Stern Architects (RAMSA) in New York as a research and writing associate. He assisted in image research for design projects, as well as for Stern's books, Paradise Planned: The Garden Suburb and the Modern City (2013) and Pedagogy and Place: 100 Years of Architecture Education at Yale (2016). Kevin also worked at Kent Bloomer Studio in New Haven, Connecticut, on the study, design, and fabrication of architectural ornament.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

The History of American Architecture lecture series is presented by Cranbrook Center for Collections and Research. The fee includes admission to all five lectures. Although the lectures build on each other, attendance at all five lectures is not required. Regretfully, discounted tickets cannot be sold to individual lectures and admission cannot be transferred to other people.

The lectures will begin promptly at their scheduled times and will be followed by a ten-minute Q&A session. The morning and evening lecture will be largely the same. There are no written assignments or evaluations.

In-person attendees may choose to attend the lectures virtually. Unfortunately, due to space limitations, virtual ticket holders may not attend in-person lectures.

This lecture series is eligible for American Institute of Architects Continuing Education credits (AIA/CES). The lecture series is only eligible for Elective credits, not Health, Safety, and Welfare units. Each lecture is one Learning Unit (LUs) for a total of five LUs for Elective credits. AIA members must log into aia.org to self-report their education. Paper forms are not accepted or used by AIA CES. Please call your local AIA chapter for more information.

INFORMATION FOR VIRTUAL ATTENDEES

On the Friday prior to the lecture date, registered participants will receive an email with instructions on how to join this virtual experience. A reminder will be sent one hour prior to the start of the lecture. We are limited to the number of virtual attendees and each registration is unique. Please do not share the login link with others.

We appreciate your support of the Center by purchasing tickets for each viewer in your household.

INFORMATION FOR IN-PERSON ATTENDEES

Cranbrook Art Museum is accessed through Cranbrook's main entrance at 39221 Woodward Avenue. Free parking is available on the east side of the Art Museum and in the parking deck located midway between Cranbrook Art Museum and Cranbrook Institute of Science. Attendees that would like access to the Art Museum's barrier-free entrance (through the New Studios Buildings) will need to make advance arrangements with the Center the week before each lecture by emailing center@cranbrook.edu.

SNOWDAY PLAN

In case of snow or inclement weather, the in-person lecture will be held live online. If the in-person option needs to be cancelled, registered attendees will be sent an email by 3:00pm on the day of the lecture. If Cranbrook Schools are closed for the day, or close early, the evening in-person option also will be cancelled and attendees will be sent a link to attend the virtual lecture.

For additional information in advance of the lecture, please email center@cranbrook.edu or call the Center at 248.645.3307.

PHOTO CREDITS

Banner Image: The Ideal City - Urbino, Piero della Francesca, circa 1480. Oil on panel, 26.6 inches x 94.2 inches, Galleria Nazionale delle Marche Urbino; Retrieved from cgfa.sunsite.dk.

Radburn Garden Homes, City Housing Corporation, 1927, Radburn, New Jersey; Courtesy of Rockefeller Archive Center.

Foundry Apse, West Housing, and the Vaults of Arcosanti, Paolo Soleri, circa 1973, Yavapai County, Arizona; Courtesy of the Cosanti Foundation.

Round Stone Barn at Hancock Shaker Village, 1826, Pittsfield, Massachusetts; Retrieved from hancockshakervillage.org.

Roycroft Inn, Elbert Hubbard, 1895, East Aurora, New York; Photography by Gross & Daley; Retrieved from artsandcraftshomes.com/travel.

The General Motors Pavilion "Futurama" designed by Norman Bel Geddes for the 1939 New York World's Fair, Flushing Meadows-Corona Park, Queens, New York, 1939-1940 (demolished); Photography by Peter Campbell/Corbis; Retrieved from Viewing.NYC.

Repairing a dome in Drop City, outside Trinidad, Colorado, circa 1966; Retrieved from joncannon.co.uk.

Rendering of Houston-Variations Project, HOME-OFFICE (Daniel Jacobs, Brittany Utting), 2022; Courtesy of HOME-OFFICE.

Kevin Adkisson, December 2024; Photography by Ayako Aratani, CAA Studio Manager, Industrial Design; Courtesy Cranbrook Center for Collections and Research.

Croquet at Radburn Garden Homes, City Housing Corporation, 1927, Radburn, New Jersey; Courtesy of Rockefeller Archive Center.