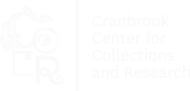

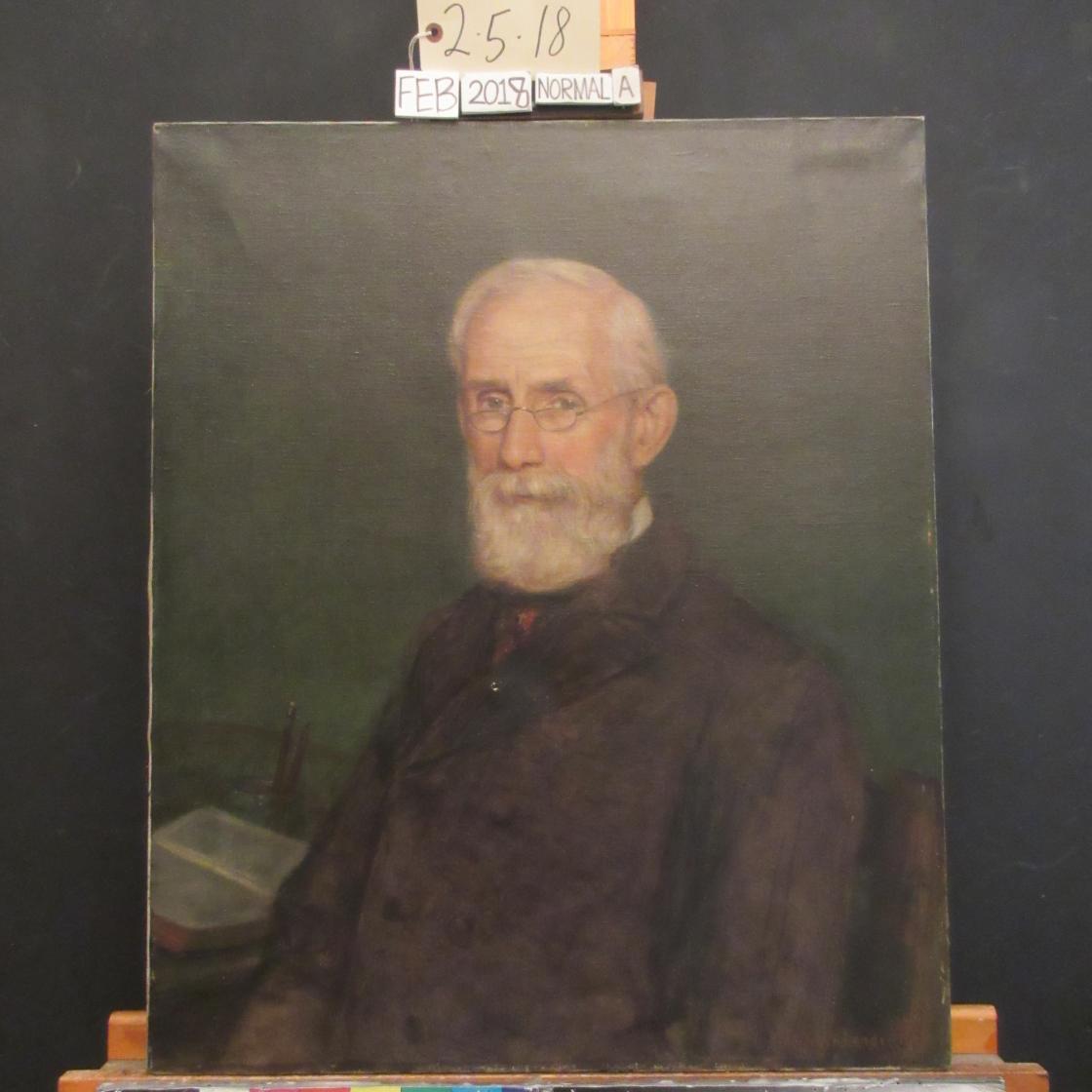

Portrait of Henry Wood Booth

Oil on canvas (signed, lower right: Robt. J. Wickenden 1906; inscribed, upper right: HENRY WOOD BOOTH / AET. LXX)

Canvas: 29-1/2 x 24-1/2 inches

Robert John Wickenden (Artist)

(Born July 8, 1861, Rochester, Kent, England; died November 28, 1931, Brooklyn, New York)

Provenance: Clara Gagnier Booth and Henry Wood Booth (1906 to circa 1930); Ellen Scripps Booth and George Gough Booth (circa 1930 to 1949); Carolyn Farr Booth and Henry Scripps Booth (1949 to 1988); Cranbrook Educational Community (1988 to present)

Cranbrook Center for Collections and Research, Cultural Properties Collection, Thornlea House; Bequest of Henry Scripps Booth and Carolyn Farr Booth (TH 2013.201)

The 2018 conservation treatment of the painting and its original frame was funded through a directed gift from John Lord Booth II, the great grandson of Clara Gagnier Booth and Henry Wood Booth.

Robert J. Wickenden, Portrait of Henry Wood Booth, 1906. Photography by Conservation & Museum Services Inc.; Courtesy Cranbrook Center for Collections and Research.

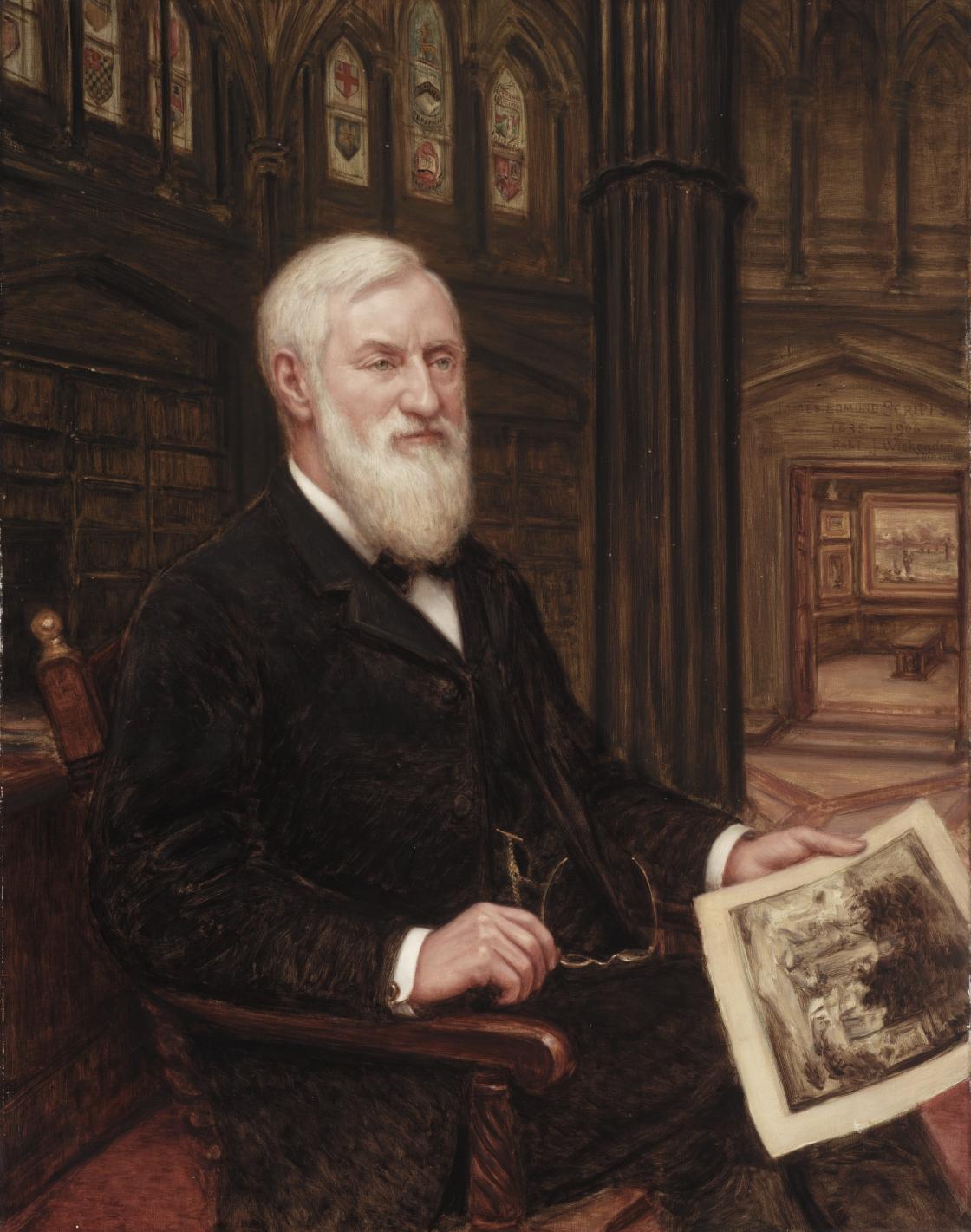

One hundred years ago, Robert J. Wickenden was a force in his field. Celebrated as a Renaissance man, the artist was an etcher, a painter of portraits and landscapes, an amateur poet, a photographer, a widely-published art critic, and a respected art dealer and consultant. Long before the age of jet travel, he was a globetrotter, living for extended periods of time on both sides of the Atlantic, while also traveling back and forth between England, France, Canada, and the United States.1 In 1884, his painting of the forest of Fontainebleau, La Glaneuse en Forêt, hung next to a portrait by James McNeill Whistler at the Paris Salon,2 and on July 30, 1890, he attended the funeral of Vincent Van Gogh in Auvers-sur-Oise where he arranged for the artist’s hearse from a neighboring village.3 Although largely unknown today, during his lifetime he was recognized as a man of talent and ambition, an artist who had a knack for being where he should be all the time. Just how did Wickenden end up painting this portrait of Henry Wood Booth (1837-1925), the father of Cranbrook’s co-founder George Gough Booth? All clues point to James Edmund Scripps, a founder of the Detroit Evening News and George Booth’s father-in-law.

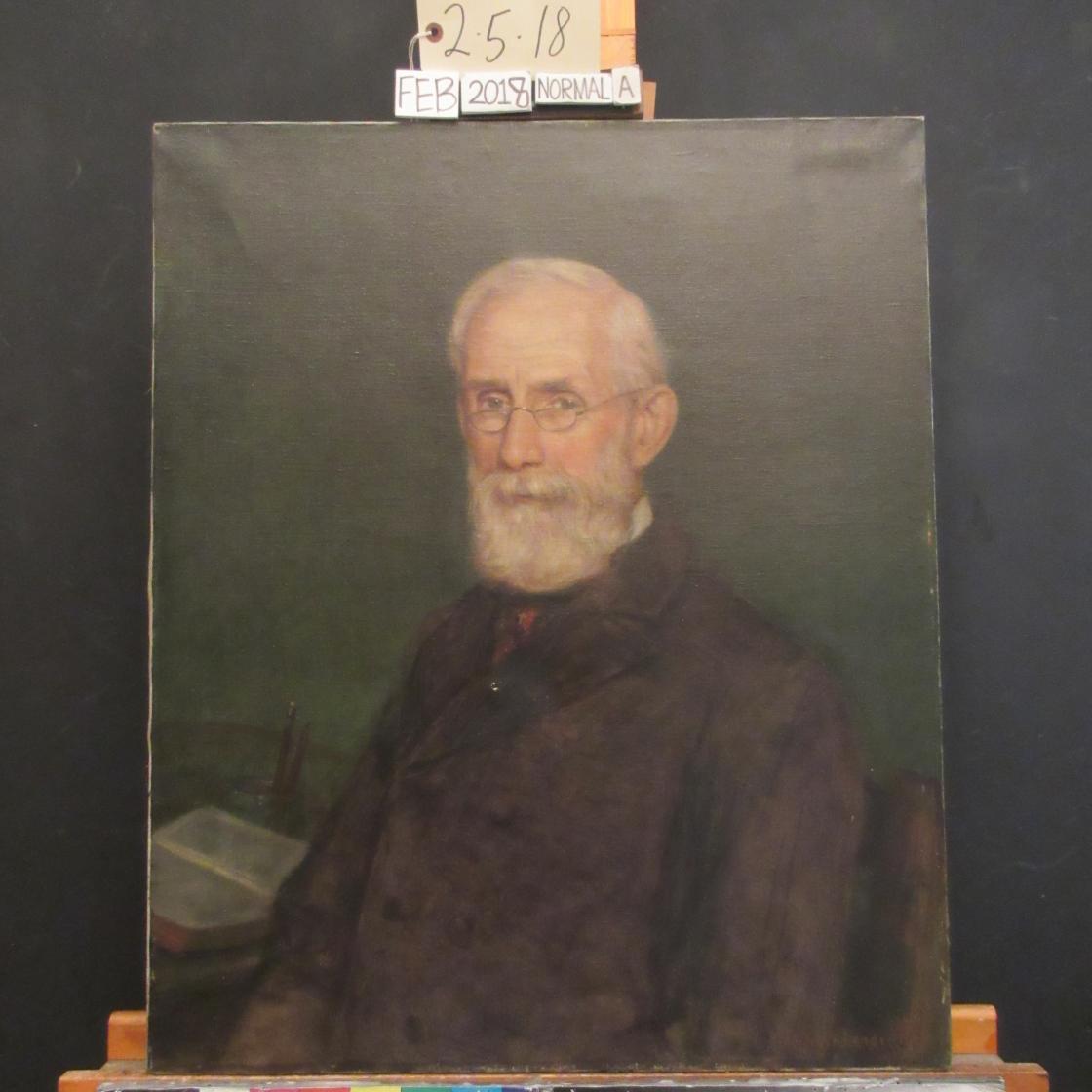

Robert J. Wickenden, James Edmund Scripps, 1907, oil on canvas (58 x 36 inches). Detroit Institute of Arts, Gift of the Estate of James E. Scripps, 07.2. Photography Courtesy The Detroit Institute of Arts.

Born in Kent County, England (where, coincidentally, Henry Booth also was born), Wickenden moved to the United States when he was twelve, joining an uncle in Toledo. Within a few years, he apprenticed with a photography firm before striking out on his own and establishing a photography studio in Toledo and then Dundee, Michigan (midway between Toledo and Ann Arbor). By 1880, he was living in Detroit and developing a career as a painter and a printmaker. Perhaps through connections he made at the Detroit Sketching Club (which enjoyed the support of James Scripps),4 Wickenden quickly became a go-to artist for Detroit’s movers and shakers known for his landscapes, portraits, and eventually, after he moved to France, his expertise as a dealer of works by contemporary French artists. In 1881, he painted a portrait of the businessman and former Michigan Governor John Judson Bagley,5 and in 1889 he sold etchings by Charles-François Daubigny to Detroit industrialist Charles Lang Freer. In the case of Scripps, the newspaper publisher bought Wickenden’s painting of the forest of Fontainebleau6 and at least one work by Daubigny, loaned the artist money, commissioned him to paint his own portrait, and asked him for advice on the selection of the fifty paintings that he gave to the nascent Detroit Museum of Art (now The Detroit Institute of Arts) as the basis of the museum’s founding collection.

Robert J. Wickenden, Self Portrait, 1894, lithograph (18 x 16 cm). Private Collection, Montréal, Canada. Photography Courtesy Ken Watson.

In December 1906 and January 1907, after living in France and Canada before moving to Bethel, Connecticut (while maintaining a studio in New York City), the artist was back in Detroit painting a replica of Scripps’s portrait to hang in the museum.7 It was on this same trip that he painted the portrait of Scripps’s friend and relative through marriage, Henry Booth.

The portrait of Henry Booth, painted by Wickenden with especially soft brushwork, shows a thoughtful man looking out over his reading glasses at the viewer. He wears a somber brown jacket over a white shirt, with a small gold cross resting on a crimson tie. A book sits open on a table in the lower left corner of the painting, behind which two wood-cased lead pencils, one with a white rubber eraser, lean in a glass jar.

Robert J. Wickenden, Portrait of Henry Wood Booth, 1906. Photography by Conservation & Museum Services Inc.; Courtesy Cranbrook Center for Collections and Research.

Wickenden painted the portrait from life, not photographs, at the “Cottage,” Henry Booth and his wife Clara Booth’s new home, which was the existing nineteenth-century Alexander homestead on the Cranbrook estate.8 We know that it was painted in the Cottage, as well as the exact days that Henry sat for the artist, from Henry’s diary—written, of course, in pencil.9 George Booth engaged Wickenden to paint the portait of his father on December 3, 1906, no doubt to mark an upcoming milestone in Henry’s life: his seventieth birthday on January 21, 1907. In an era when the average lifespan of a man was less than forty-seven years, this was, indeed, an occasion to celebrate and commemorate with a portrait—duly inscribed with the sitter’s name and age—by a well-known artist.10 Henry sat for Wickenden a total of eight (non-consecutive) days, December 4 through December 20, during which the artist and sitter seemed to have developed a comfortable relationship. Following the fourth sitting, the artist sang for Henry and Clara in the evening and on the Saturday of the seventh sitting, December 15, Wickenden joined a family dinner that included George and his wife Ellen Scripps Booth and three of their five children: Grace, Warren, and Harry. The elder Henry Booth notes that they all left after “5 o’clock tea,” returning to Detroit where Wickenden was staying and George and Ellen still lived with their family on Trumbull Avenue, the street on which Henry and Clara also lived before moving to the Cottage at Cranbrook.11

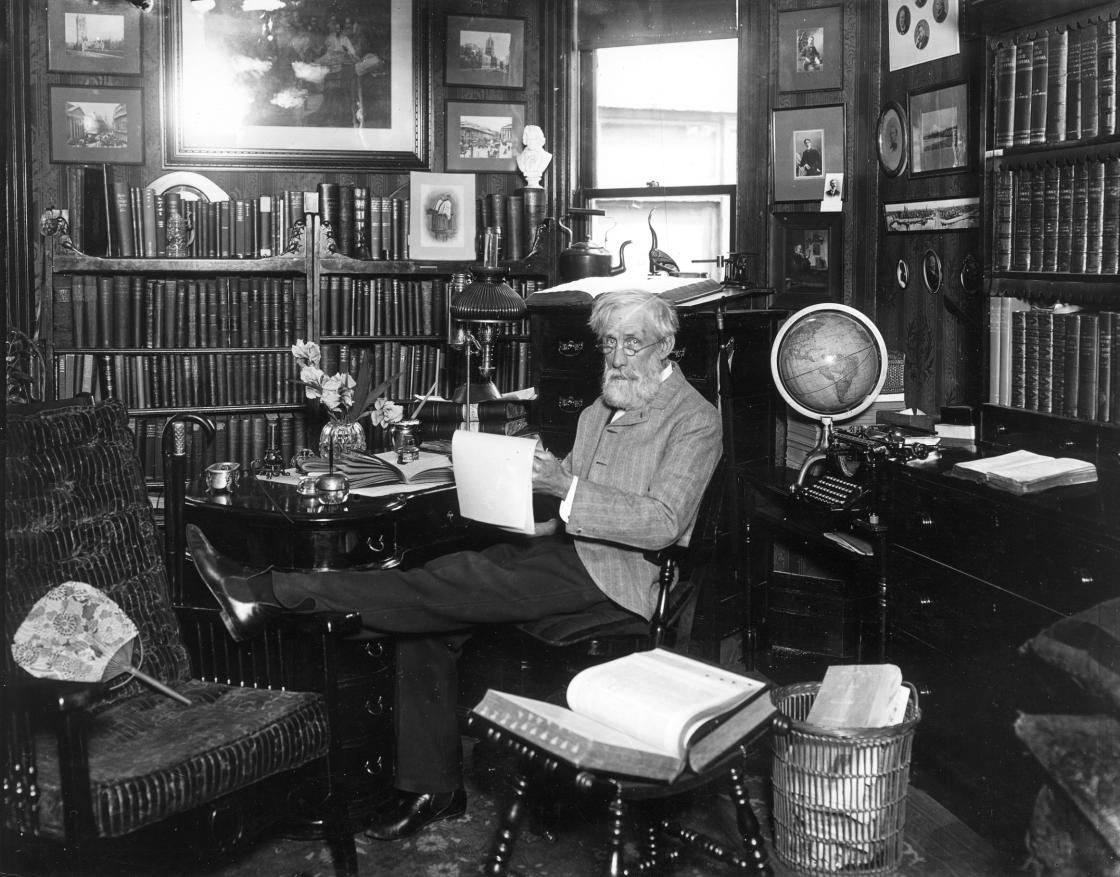

Henry Wood Booth, circa 1912. Photograph Collection of Cranbrook Archives (CC278-1). Henry Booth is standing in the yard of the Cottage at Cranbrook. The view is of the east side of the house, which faced Cranbrook Road.

While Henry Booth’s diary tends to stick to the facts, including a record of the daily weather conditions, he notes one moment of debate concerning the painting in the entry for Thursday, December 6, the third day of the sitting: “Brook swollen from rain, cold and stormy but barely freezing. Returned from Detroit. Sat to [sic] Mr. W most of the day. George came out. Decided not to use specticles [sic] in portrait.” In spite of this emphatic note about the spectacles—Henry underlined “not”—the artist or the sitter, or perhaps even the patron, the sitter’s father, decided the portrait should show Henry wearing his reading glasses. Like the book, the pencils, and the cross, the glasses are an important attribute. This is not a depiction of a man of power, but rather a man of intellect: a reader, a writer, and a man of faith.

Henry Booth wrote many articles and essays during his lifetime, including his most well-known publication, The Snake Scotched: A Suggestion to Teetotalars and Temperate Drinkers for a Settlement of the Drink Controversy on the Basis of Partial or Progressive Prohibition. (Even though Henry made a living as a distiller during his first years in North America, he joined the Temperance Movement and crusaded for Prohibition.)12 While Wickenden was painting his portrait, Henry was writing essays on “religion and morals,” working until midnight many nights. Like the essays that he later compiled as The Snake Scotched, his weekly essays on religion were published in the pages of the family newspaper, the Detroit News-Tribune, under the nom de plume “Laic.” His December 16, 1906, essay (number 80 in the series), cogitated on, among other things, the role that the printed word, including newspapers, had played in the decline of church attendance, noting: “The costly edifices which the Protestant Episcopal church is now erecting in this country may attract the idle rich, but they will never draw the industrious reading poor, as such buildings did in the middle ages, when very few could read and all religious instruction was auricular—conveyed from the mouth of the speaker to the ear of the listener—and so people had to go to church to get it.” Perhaps this was a not so veiled comment on the planned building of St. Paul’s Episcopal Cathedral on Woodward Avenue in Detroit, an idea that began to be discussed publicly in 1906 with the election of Bishop Williams.13 One can only imagine what Henry would write today about the impact of digital technologies and social media on the decline of printed newspapers. Based on what he wrote in 1906, it sounds like he might have argued in favor of digital over analog and technology’s ability to preach to the masses.

Henry Wood Booth, circa 1904. Photograph Collection of Cranbrook Archives (E222). Henry Booth is seated in his study in his home on Trumbull Avenue in Detroit, where Clara Booth and he lived before moving to the Cottage at Cranbrook.

Cranbrook House Reception Hall, circa 1916. Photography Collection of Cranbrook Archives (E452). The portrait of Henry Booth by Robert J. Wickenden is hanging over the fireplace.

This portrait is believed to have hung in at least three places at Cranbrook: in the Cottage; over the fireplace in the Reception Hall of Cranbrook House; and over the fireplace in the large drafting room of Thornlea Studio, north of Thornlea, the home of Carolyn Farr and Henry “Harry” Scripps Booth, Henry Wood Booth’s grandson and namesake.14 With the painting and its original frame newly conserved, the portrait has been returned to Cranbrook House15 where Henry Booth can once again look up from his book, glance over his spectacles, and address visitors with his thoughtful, watchful gaze.

Gregory Wittkopp

Director

Cranbrook Center for Collections and Research

April 2019

FOOTNOTES

1 Unless noted otherwise, all information about the artist comes from Susan J. Gustavison’s unpublished manuscript, “Robert J. Wickenden (1861-1931) and the Late Nineteenth-Century Print Revival” (master’s thesis, Concordia University, Montréal, Québec, Canada, 1989). I thank Ken Watson, who scanned and made a computer transcription of Gustavison’s original printed manuscript, for sharing the document with me and placing me in contact with Gustavison. All page numbers refer to a copy of the computer transcription in the painting’s object file with the Cranbrook Center for Collections and Research.

2 Foreword to the exhibition catalog Forty-eight Landscapes in Oil and Watercolour by Robert J. Wickenden (Toronto: The Carroll Gallery Limited, 1923). The Foreword is quoted in its entirety in Gustavison, “Robert J. Wickenden,” Appendix C: Robert J. Wickenden Exhibitions, 175-76.

3 Gustavison, “Robert J. Wickenden,” Appendix B: Robert J. Wickenden (1861-1931) Chronology, 134.

4 Gustavison, “Robert J. Wickenden,” Introduction, 1, and “Detroit Artist Robert J. Wickenden, Now of New York, Was Formerly a Detroiter,” Detroit News Tribune, Magazine Section, Sunday, January 6, 1907.

5 Since 1973, the Bagley portrait has been in the collection of the Detroit Historical Society. I am grateful to Jeremy Dimick, Manager of Collections, for sharing information about this portrait with me.

6 “Detroit Artist Robert J. Wickenden, Now of New York, Was Formerly a Detroiter,” Detroit News Tribune, Magazine Section, Sunday, January 6, 1907.

7 Wickenden painted the original portrait in 1904 while the replica was completed in 1907. The 1907 replica is the version that has remained in the collection of The Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA). For more information, see the DIA’s entry on their website.

8 The Cottage remained a part of the Cranbrook estate until 1930, when Clara Booth died and the Cottage was demolished.

9 Henry Wood Booth, Diary (October 1906 to July 1908), Cranbrook Archives, Henry Wood Booth Papers, Box 1:10.

10 For one citation of lifespans in the early twentieth century, see Andrew Noymer, accessed January 20, 2018. The inscription includes the term aet., which is the abbreviation of the Latin word aetatis, meaning “of the age of” or “aged.” The abbreviation is followed by the Roman numerals for seventy.

11 The groundbreaking for Cranbrook House did not take place until January 4, 1907. Henry Wood Booth, Diary (October 1906 to July 1908), Cranbrook Archives, Henry Wood Booth Papers, Box 1:10.

12 See Leslie S. Edwards’s Collections Highlights essay, “The Snake Scotched,” published on the Center’s website.

13 The cathedral was dedicated in 1911. See “Building the Cathedral by Samuel Marquis” on The Cathedral Church of St. Paul website.

14 While we assume the painting remained in the Cottage after Wickenden finished it, we cannot confirm where it hung until it was moved to Cranbrook House, sometime after the home was completed in 1908. The painting appears on the 1914 Cranbrook House Inventory. Henry Scripps Booth inherited the painting after his father died in 1949.

15 In July 2018, the painting was hung in the Living Room, to the right of the window. Its return to the Reception Hall awaits the completion of a comprehensive furnishings plan for Cranbrook House.

Banner photo by P.D. Rearick, CAA '10