Frank Lloyd Wright Smith House

SMITH HOUSE

HOME OF MELVYN AND SARA SMITH, 1950-2005

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT, ARCHITECT

1950/1968

This low-slung, cypress wood and brick home from the hand of America’s foremost architect is the realized dream of Melvyn Maxwell Smith and Sara Stein Smith. Teachers in Detroit Public Schools, the couple built the house through radical penny-pinching, perseverance, and a dedication to their dream. By the 1960s, Smithy and Sara were regular guests at Cranbrook Academy of Art events, supporting students at art sales and auctions and filling their home with Cranbrook art.

This tradition continues in Speculative Histories. For this exhibition, current Cranbrook artists and designers have engaged with stories about the Smiths, the dramatic life of Wright, the collections assembled within this home, or simply the powerful spirit of the place.

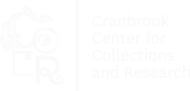

Exterior

Set on a bucolic three-acre lot among oak trees and overlooking an undulating pond, Smith House embodies Wright’s goal of creating an organic architecture connected to nature. Ed Ryan subverts both the naturalism of the site and the high art architecture of the house with his window vinyl, a nod to both the manic advertising language of estate sales and Craigslist advertisements and the commercial signage of found on auto shops and strip malls along nearby Woodward Avenue. A waving tube man completes the juxtaposition of art and commerce. On one of the few corners of the garden without an existing sculpture, Grace Makuch has suspended a piece of the landscape within an impossible-to-water terrarium as commentary on Wright’s complicated personal history. Across the rear patio, Jessy Slim has placed sheet steel studies formed from the weight of her body on the material; her process of bending and undoing registers the mark of her action.

LIVING ROOM

In a room chockablock of wood, glass, and ceramic objects, Artist-in-Residence Ian McDonald imagined the Smiths’ expanding their collection into the present day and onto the last remaining empty flat surfaces: Wright’s signature flexible furniture form, the hassock. McDonald also brought down from the bookshelf a vessel by legendary Cranbrook Artist-in-Residence Maija Grotell to join his grouping. On the desk behind sits Kate Auman’s reflection on disability and death positivity, Afterlife, a book-sized sculpture with two portals. One portal looks to a portrait of the artist’s mother, the other features a set of black steps—a prominent architectural feature on Cranbrook’s campus but a significant barrier to artists, like Auman, with limited mobility.

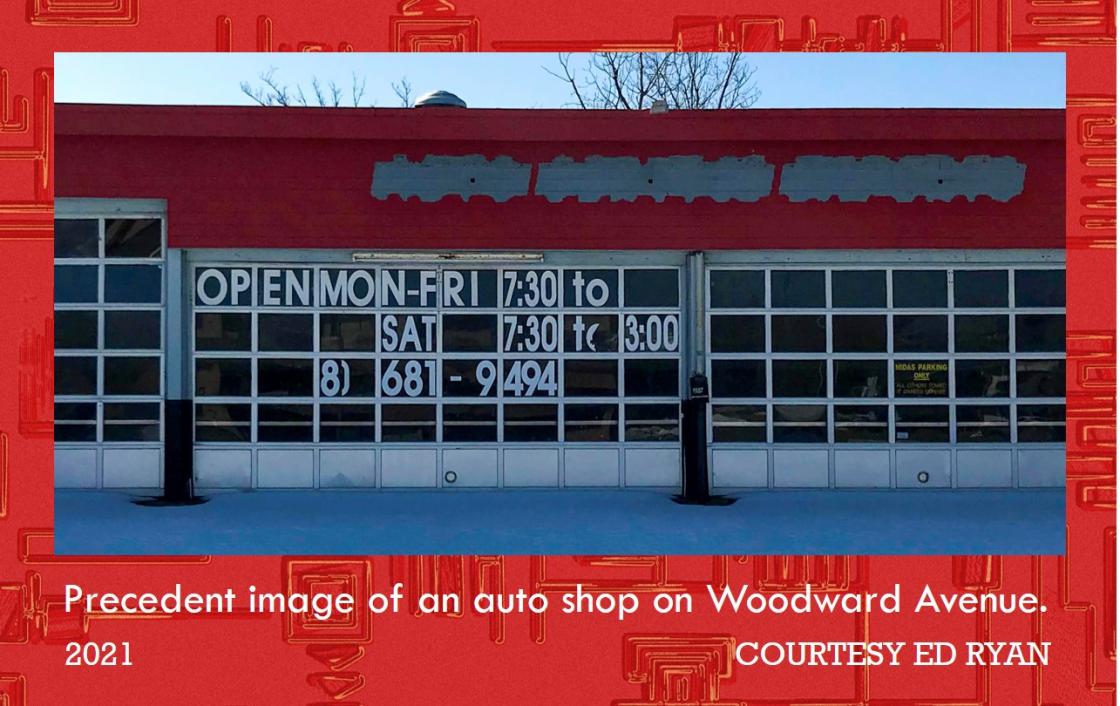

On the bookshelf, a skate deck designed by Lindsey Camelio combines graphic motifs of Eliel Saarinen and Frank Lloyd Wright for an imagined trip out west, entitled Frank and Eliel’s Excellent Adventure. In the 1970s, Melvyn Smith hung a Japanese furo (portable brazier or kettle) in his fireplace. This charcoal-heated kettle should in fact sit directly on the ground, not over an open fire; Neva Gruver has whimsically added flying copper teacups to this levitating kettle.

Ian McDonald

Ian McDonald, Ceramics Artist-in-Residence

Ceramic, steel

Dimensions variable

2020-2021

Shown with

Vase

Maija Grotell, Ceramics Artist-in-Residence 1938-1966

Glazed red stoneware

9½ x 3½ inches

Mid-20th century

Gift of the Towbes Foundation, Smith House Collection

Kitchen

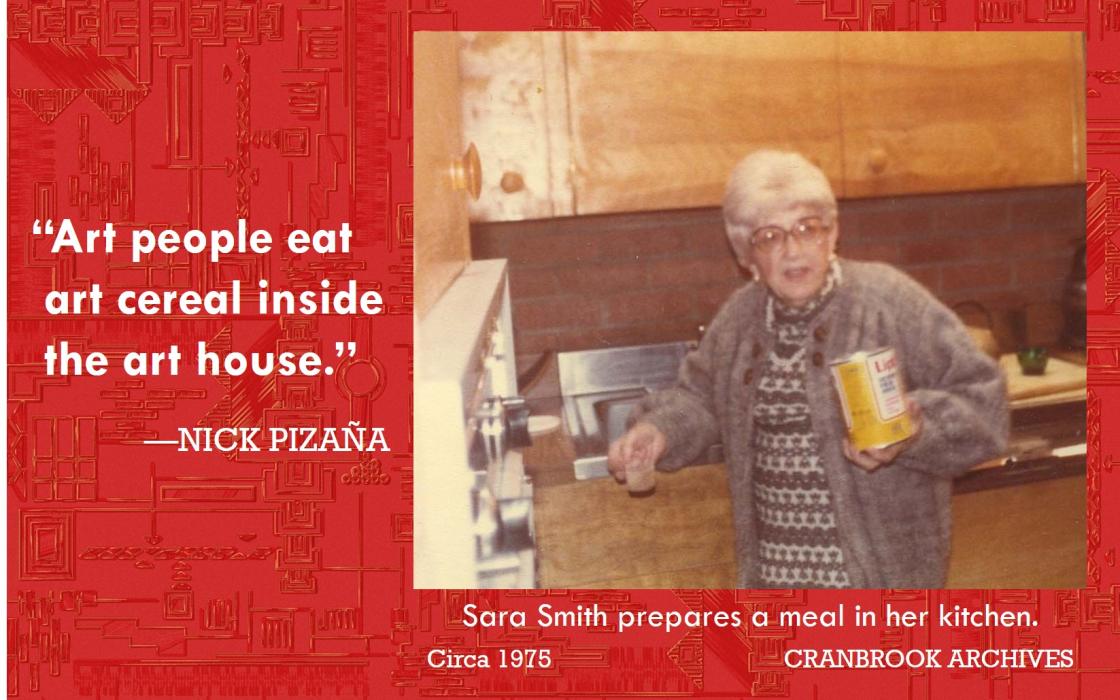

In the kitchen where Sara Smith whipped up her famously sweet lemonade, prepared her offering of green grapes for guests, and cooked such midcentury cuisine as Campbell’s Tomato Soup or boiled hot dogs, Lindsey Camelio presents her Egg Scarf, placed casually as if Sara has just tossed it aside in the heat of cooking. On the kitchen counter sits Nick Pizaña’s reflection on both midcentury commercial art and the paradox of a house that cannot be lived in through his cereal boxes that cannot be opened and cereal that cannot be eaten. Opposite, Daniel Smith’s hand-pressed tiles mirror Wright’s own red signature tile, given by the architect to his clients and attached to the house near the front door. Smith intended his tiles, made up of his own fingerprints, to inspire questions about the mark of Wright (or any architect) on our world. In the dining room, Mandy Moran placed live-edge occasional tables with 3D-printed lamp prototypes.

Lindsey Camelio

Lindsey Camelio, 2D Design 2017, Studio Fellow 2020-2021

Digitally printed scarf

26 x 26 inches

2021

Shown atop

Untitled (Multimedia Sculptural Screen)

Glen Michaels

Wood, tile, cut stone, bronze, metal, paint, and found objects

78¾ x 92½ inches

1967

Gift of the Towbes Foundation, Smith House Collection

BEDROOMS AND BATHROOMS

Wright believed in a firm division of public and private space within the home, and this division is clearly reflected in the narrow hallway leading to Sara Smith’s intimate study. Here, Jo Lobdell’s sculpture responds to Sara’s love of talking on her red phone for hours each day. As Lobdell writes, her piece is "responding to that energy that was produced in the house through her conversations. This work engages the presence that communication holds in a space." On the bookshelf, Nelly Kate topped a bust of Frank Lloyd Wright with a helmet painted “MOD. VIII 15-1914.” This date, written like a scripture, refers to the tragic Taliesin massacre at Wright’s Wisconsin home when his partner and six others were murdered. Kate hoped to bring forward the entanglements of Modernism’s fraught history with race, class, and memory.

In the bathrooms, Kelly Agius presents a tool that captures and contains past presence through a hypothetical filtration process that removes undesirable memories, while Katie Severson presents a multicolored mass inspired by mushrooms and molds. Nearby, the Owner’s Bedroom sees the clever replacement of the Smiths’ folding TV tray nightstand for one where the contents of the stand have been painted on using a trompe-l'œil technique by Clara Nulty. Tucked into bed are four Butch Flowers by Print Media Artist-in-Residence Emmy Bright.

Emmy Bright

Emmy Bright, Print Media Artist-in-Residence

Double sided silkscreen on paper

22 x 7 inches

2017

SUNROOM AND SITTING ROOM

Maura Latty and Brian Kovach’s photograph of the artist challenges Wright’s specific utopian vision and aesthetic, particularly the way his architectural scale neglects othered bodies. Their celebration of queer bodies and queer aesthetics reflects the radical love Sara Smith expressed to others, including the many young gay artists she and Smithy supported through friendship and patronage.

In the back sitting room, Bonnie Qinyue Xue created a wax sculpture to infill one of the openings of the vertical folding screens added throughout the house in 1968. She writes that this is both “an illusion of filling in a hole” and “an unanswered promise." Fabiana Chabaneix was inspired by stained glass, a practice Wright abandoned by the early-1920s, to filter light coming into the home through different opacities. Imagining the Smiths sitting down to karaoke on their television, Noelle Choy’s work engages with the idea of celebrity and popular culture entering into a house full of art objects. Beside one of Sara Smith’s permanent botanical arrangements, Carmichael Jones added a glass sculpture, etched with a constellation and holding its own fake plant: AstroTurf.

PHOTO CREDITS

(concentrate on your desires) photograph by Brian Kovach, Photography 2022. Courtesy of the Artist.

Color photography by Eric Perry, Courtesy Cranbrook Center for Collections and Research.

Historic photographs Cranbrook Archives, Cranbrook Center for Collections and Research.